(This essay is too long for email. Please click the title, to read the full thing on the website or in the app. Or print it out and sit with it slowly, if you prefer! I have some shorter pieces, continuing the examination of the virtues, coming soon.)

Early in the account of the creation of the worlds in the Vǫluspá, we find a passage which has troubled some modern commentators:

The Æsir met on Idavoll Plain,

high they built altars and temples;

they set up their forges, smithied precious things,

shaped tongs and made tools.(Vǫluspá v. 7, trans. Larrington)

Here, we see unambiguously that the Gods themselves are engaging in religious practice, with the explicit mention of temples and altars, and the clear presumption that offerings are being made on those altars (since, after all, that’s what an altar is for). The noted archaeologist of the Viking Age, Neil Price, remarks (italics in the original):

One other dimension of the Gods’ lives is intriguing. Strangely, Asgard also contained temples, cult buildings where the Gods themselves made offerings — but to what or whom? The mythology of the Vikings is one of only a tiny handful in all world cultures in which the divinities also practiced religion. It suggests something behind and beyond them, older and opaque, and not necessarily ‘Indo-European’ at all. There is no indication that the people of the Viking Age knew what it was any more than we do.1

In this essay, I’d like to explore what’s going on when the Gods make offerings: partly in reaction to Prof. Price’s puzzlement, but also more broadly, as an exercise in comparative theology, and even a gesture toward some of mysteries of the Goddess Freyja which can be glimpsed through that theological undertaking. In particular, I’d like to suggest that we can get some help by looking at the phenomenon of the Gods making offerings in the Hellenic theology: both in mythic narrative, and in the analysis of those mythic narratives offered by philosophers working within the Platonic tradition.

I should emphasize that this is only one set of possibilities, among many others which are contained within, or made possible by, the mythic narrative. Such myths as we find in the Vǫluspá (and in the Northern theology, like any robust theological tradition, more broadly) are always inexhaustible: no interpretive account, and certainly not this one, could ever hope to capture all that the myths, and the Gods who are the fountains of those myths, have to offer.

I. Divine Offerings in the Hellenic Theology

I’ll begin by admitting to an initial puzzlement with Prof. Price’s puzzlement, as it were. While an extensive project of theological comparison across a large number of traditions is well beyond the scope of this essay (and well beyond my own expertise), the other polytheist theological tradition which I know best, that of Hellenic polytheism, has an abundance of mythic accounts that present the Gods and Goddesses as pouring libations or otherwise making offerings and engaging in religious practice. Here, I’ll consider two branches of this: from the archaeological record, in the form of artistic depictions in pottery, and from the literary record, in the mythic vision at the core of Plato’s Phaedrus. Here of all places, Plato is writing as a mythographer, far more than a philosopher, as the text itself makes clear: as his companion observes in some amazement, the mythic vision is declaimed by a Socrates who has been wholly caught up in divine ecstasy, speaking in an inspired frenzy. This method of “reading” both material artefacts and written words as together declaiming this theology, meanwhile, is an approach to which scholars like Price, quite rightly, have shown themselves highly sympathetic; it is in fact the explicit method of Price’s previous (and highly recommended!) book on Viking Age sorcery, The Viking Way.

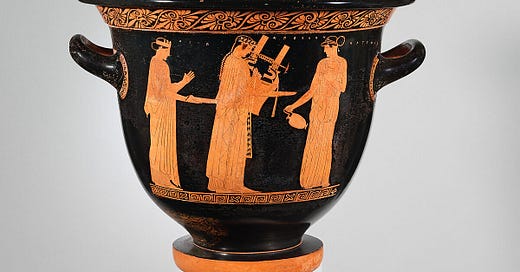

We can begin with a cursory glance at Greek ceramics. Above, we find Apollon, Artemis, and their mother Leto together pouring libations, while below, we see Zeus, Hera, and Athena doing likewise.

On both of these vessels, in addition to the Gods and Goddesses giving their own libations, we also find a second scene, in which unnamed mortals are offering their own libations to the Gods. The interpretive captions for these two items, from the curators at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, note that “the conceit of depicting [both] Gods and mortals preparing libations is a recurrent theme” in classical Attic artwork, and that the juxtaposition of divine and human offerings “provides a remarkably graphic illustration of the ancient Athenians’ sense that a commonality in belief and practice existed between the mortal and divine worlds.”

We should also note that such artistic depictions seem not to be restricted to any particular group or class of deities: this is something that, in principle, any God or Goddess might do, with any other God or Goddess as the recipient of the offering. Here, for instance, we find Dionysos pouring a libation, which might be considered a form of self-offering, from the God who is some sense is the wine and grape, the flower and the fruit.

Here, I’ve relied upon images from the Met for the simple reason that the Museum has generously placed them into the public domain; and so, my thanks to them! Once we consider other collections, and then estimate what small fraction of the artefacts once produced have survived the millenia at all, it becomes apparent just how widespread the artistic practice, and corresponding theological understanding, were in the ancient world.

With those images in mind, we can turn to the literary record. Plato’s Phaedrus was written squarely in-between the time when the first two vessels were painted, and the time of the latter depiction of Dionysos. In the central mythic episode of Plato’s dialogue, we hear a divinely-inspired Socrates describe first a chariot procession around the heavens, in which each of the Gods and Goddesses leads a train of followers around the rim of the heavens, where the divine leaders and their followers alike feast their gaze upon beauty itself, truth itself, and so forth. The followers in this procession include, but are by no means limited to, human souls; indeed, we humans are explicitly the least of those who take part, even struggling to do so, in sharp contrast to the daimones (or intermediary spirits) who occupy a place between us and the Gods, and who (like the Gods, but unlike us) experience no difficulty in keeping their chariots travelling smoothly. Having enjoyed this celestial vision, the Gods then retire to a banquet, where they feast one another.

The depiction of these scenes is beautiful and moving; here I quote Thomas Taylor’s translation at some length:

There is a natural power in the wings of the soul, to raise that which is weighty on high, where the genus of the Gods resides. But of every thing subsisting about body, the soul most participates of that which is divine. But that which is divine is beautiful, wise, and good, and whatever can be asserted of a similar kind. And with these indeed the winged nature of the soul is especially nourished and increased: but it departs from its integrity, and perishes, through that which is evil and base, and from contraries of a similar kind.

Likewise Zeus, the mighty leader in the heavens, driving his winged chariot, begins the divine procession, adorning and disposing all things with providential care. The army of Gods and daimones, distributed into eleven parts, follows his course; but Hestia alone remains in the habitation of the Gods. But each of the other Gods belonging to the twelve,2 presides over the office committed to his charge. There are many, therefore, and blessed spectacles and processions within the heavens, to which the genus of the blessed Gods is converted as each accomplishes the proper employment of his nature. But will and power are the perpetual attendants of their processions: for envy is far distant from the divine choir of Gods.

But when they proceed to the banquet, and the enjoyment of delicious food, they sublimely ascend in their progression to the subcelestial arch. And, indeed, the vehicles of the Gods being properly adapted to the guiding reins, and equally balanced, proceed with an easy motion: but the vehicles of other natures are attended in their progressions with difficulty and labour. […] And in this case labour, and an extreme contest, are proposed to the soul. But those who are denominated immortals, when they arrive at the summit, proceeding beyond the extremity of heaven, stand on its back: and while they are established in this eminence, the circumference carries them round, and they behold what the region beyond the heavens contains.

But the supercelestial place has not yet been celebrated by any of our poets, nor will it ever be praised according to its dignity and worth. It subsists, however, in the following manner; for we should dare to affirm the truth, especially when speaking concerning the truth: without colour, without figure, and without contact, subsisting as true essence, it alone uses contemplative intellect, the governor of the soul; about which essence, the genus of true science, resides. As the dianoëtic power, therefore, of divinity revolves with intellect and immaculate science, so likewise the dianoëtic power of every soul, when it receives a condition accommodated to its nature, perceiving being through time, it becomes enamoured with it, and contemplating truth, is nourished and filled with joy, till the circumference by a circular revolution brings it back again to its pristine situation.

But in this circuit it beholds justice herself, it beholds temperance, and science herself: not that with which generation is present, nor in which one thing has a particular local residence in another, and to which we give the appellation of beings; but that which is science in true being. And, besides this, contemplating and banqueting on other true beings in the same manner, again entering within the heavens, it returns to its proper home. But, when it returns, the charioteer, stopping his horses at the manger, presents them with ambrosia, and together with it, nectar for drink. And this is the life of the Gods.

But, with respect to other souls, such as follow divinity in the best manner, and become similar to its nature, raise the head of the charioteer into the supercelestial place; where he is borne along with the circumference; but is disturbed by the course of the horses, and scarcely obtains the vision of perfect realities. But other souls at one time raise, and at another time depress, the head of the charioteer: and, through the violence of the horses, they partly see indeed, and are partly destitute of vision. And again, other souls follow, all of them desiring the vision of this superior place.

II. Some Comparative Interpretation

The exegesis of this passage — in its own right, in the context of the dialogue as a whole, and within Hellenic theology and the Platonic philosophic tradition — could easily fill one or many books.3 But for now, we can focus on a few key points, setting each of them in dialogue with the episode from the Vǫluspá and some recent commentary thereupon.

First, there is a focus on paradigms or exemplars. On the one hand, we see the paradigms of mundane justice, beauty, and the like, arrayed beyond the heavens, from which they are the source of justice, beauty, etc., for all those things further downstream which participate in them: beautiful souls, just actions, beautiful bodies, etc. — and not only we mortals, but even the Gods themselves gaze upon these, and are nourished thereby. Furthermore, the very way in which we partial souls are described echoes, at least in mythic or paradigmatic terms, the way that the higher daimonic kinds and the Gods themselves are described, in the image of charioteers leading a team of two horses. We thus see in words what the Met curators identify in material culture, the “commonality of belief and practice between mortal and divine worlds,” and the “blurring of boundaries … between Gods and men.”4 We can continue this comparative analysis still further, to consider the way that the divine banquet, and the pouring of offerings there, prefigure the analogous activities conducted by mortals. We can summarize all of this, in the principle that there must be a source and a paradigm for all truly existing mundane things, somewhere upstream at a supermundane level.

In her commentary on the verse of the Vǫluspá with which I opened this essay, Ursula Dronke quite aptly hits on exactly this:

The focus on the Gods becomes closer: they become more familiar, more secular. We see them in all kinds of activity — building, forging, merry-making, betting — Gods in the image of man. The poet now calls them by the cult name men use for them, Æsir, and appropriately shows them raising their own temples and altars — archetypes that men will copy — and fashioning wealth, the symbolic basis of good fortune for Gods and men.5

In light of our Platonic exegesis of the Phaedrus passage, we can say that Dronke is spot-on in her identification of these archetypes. But if we’re to carry forward consistently this notion of archetypes or paradigms — not to mention remaining within the bounds of piety — we need to correct her preceding sentence: it is not the Gods who are in our image, but rather, we who are in theirs.

Dronke’s observation that the Gods “become more familiar, more secular” is likewise interesting and apt, provided that we understand this as applying to their depiction, or to our mode of encounter with them, for the Gods themselves are eternal, and thus, unchanging.6

This “becoming familiar,” then, speaks to the way in which the Gods are always active at every level, in every element of the cosmos which they create and sustain at every moment — while also recognizing our own limited perspective, such that we are especially able to encounter and engage with them right here and now, where we are as human beings. This interplay of the continuity of divine activity, with the various levels on which that activity plays out, brings us to a second important interpretive lesson.

This relates to Dronke’s mention of a “symbolic basis.” In the Platonic tradition, it is customary to identify the tokens or symbols7 which are the marks or traces left by some particular God or other in each thing that exists. Those symbols or traces, located right here, in ourselves and in everything around us, link each of us, and every other thing in the cosmos, upstream to its particular, proper8 divine starting point. So, the Platonist would embrace Dronke’s concept, but revise the terminology ever so slightly, to make clear that the divine realm provides the basis according to which the symbols that are present here are able to function in this anagogic way.

This, in turn, brings us squarely to the chariot procession itself, divided as it is according to the individual God or Goddess who leads each group. As Plato relates the myth, the emphasis is on each chain or series as extending from the God or Goddess, through the various intermediary powers, to human souls. This is all well and good. Yet the Platonic tradition also takes a wider perspective on these divine series, extending a chain of connection, as indicated by the tokens or symbols mentioned above, all the way from each divine leader, through those intermediaries and partial souls, through the other animals, plants, and even such totally inanimate things as stones. Each of these — considered not so much as a member of a kind, but rather, as an individual — is by his/her/its very nature, part of the series of some specific, individual God or Goddess. We thus find a philosophical account of the phenomenon noted by the Met curators, when they observed “the blurring of boundaries between Gods and men,” and “the commonality of belief and practice between mortal and divine worlds.” As the Platonic tradition has understood things, there really are, and must always be, such chains of unbroken continuity all the way from the Gods to the most apparently remote corners of the material world — and from different Gods to different corners. For the Gods are present even here.

In the list just given, the mention of “partial souls” refers to us. We are so called because, unlike the higher beings who can manifest their entire nature, all at once, for all eternity, we are able only to enact one part of our nature at a time, with the corresponding need to enact different parts of our nature at different times, spread across not only a single lifetime, but even an extended series of incarnations. This part-by-part aspect of our nature — our “partiality,” as it were — will become critically important as we proceed.

Plato, and most of his heirs among the Hellenic philosophers of antiquity, quite reasonably focus on the value of identifying the God in whose series one is suspended, and living a life in accordance with that God. So, for instance, an Apollonian soul might do well to live a prophetic life, while a soul in the series of Ares might do well to live a military sort of life, a Hephaistian soul a life of craftsmanship, and so forth.

But there’s another side of this as well. When we live a life that is in accordance with some other God, then we become the offering poured out by our own divine leader, to that other God. So, for instance, when an Apollonian soul lives a Hephaistian life, that soul is all along (and always will be) Apollon’s, yet for as long as she is living that Hephaistian life, she is being given by her leader as an offering to Hephaistos. Such lives, such offerings, can take any permutations, just as in the Attic vase-paintings, there was no absolute hierarchy of which Gods poured libations to which others.

We should also note the all-important aspect of choice. As souls, we are self-movers, instigators of change and activity; while we are certainly subject to change, insofar as we are true to our nature, the most important of these changes will come from within. Thus Plato will emphasize, in the Myth of Er that closes the final book of the Republic, that the choice of each life into which we are born is entirely our own (albeit based on the character, habits, and dispositions that we have formed through the choices we’ve made in previous lives): “Virtue is independent, which every one shall partake of, more or less, according as he honours or dishonours her: the cause is in him who makes the choice, and the God is blameless.”9 And in a further echo of the patterns and paradigms that we’ve already encountered several times in this essay, strictly speaking, Plato’s statement in the Myth of Er is that we choose “the paradigm of a life.”10 It is, in some mysterious way, by our choosing that the offering from one God to another is made — a situation quite unlike that for beings situated either upsteam or downstream from us in the order of things, made possible by our free will, our self-motivity, and indeed, our partial nature.

III. The Blótgyðja of the Gods

Here, perhaps, we have both a key to some aspects of the Northern theology, and some things which the Northern tradition can, in return, offer to the Hellenic. For if indeed there is no absolute hierarchy of which Gods give offerings to which others, such reciprocity is exactly what we should expect, and hope for!

I have in mind the title which belongs to Freyja as the blótgyðja of the Gods; that is, the priestess who performs blood-sacrifices on behalf of her fellow Goddesses and Gods. For a blood sacrifice is nothing other than the offering of a life to a God, and the hallowing both of that life, and of the entire community, thereby. In Freyja’s divine activity, therefore, we can see not merely (as in the received Hellenic accounts) the offerings themselves, but the divine person who superintends this entire economy of sacrifice. In the choosing of a life (and the carrying out of that choice), the lifeblood of each of us is poured out, by Freyja’s hand, under her sacred knife, as the gift of one God to another, and when this is done worthily and well, both the individual and the larger community of Gods and mortals are hallowed thereby.

What an exquisitely beautiful and ennobling thing — as, indeed, is any fitting sacrifice, for even the word itself means “to make holy.”

And yet, is there also an aspect of being pulled away from our own Leader-God, in the course of becoming such an offering? This question led many of the late antique Platonists like Olympiodorus to suggest that there was something superior about choosing (and living) a life that accords with our own Leader-God, rather than that belonging to another. I’d suggest, though, that all of these mysteries — our being held close by our Leader-God, and our being offered by him to others — are important parts of the soul’s unfolding her part-by-part nature. We do, after all, get to do this many times, just as Freyja herself was “thrice burnt, and thrice reborn” (Vǫluspá 21).

So these two aspects of death and rebirth, immolation and restoration, are providentially united in the person of Freyja. Inspired by these mysteries, we might then ask, how is it that in being poured out upon the sacrificial altar to another God, we are both hallowed, and returned to our own proper source? For this dynamic of a gift being given, then returned to the giver, having been hallowed and transformed, characterizes even the blót that is performed by the human community.

I’d like to suggest that when we become such a sacrifice — and especially when we enter into that mindfully — it’s not so much that we’re changed into something else, as that we are working out another part of ourselves, a part that the Gods — our own leader and many others — have provided for, from eternity. For myself at least, the mysteries of Freyja bring that providential aspect to the fore, with a special emphasis on being completed in the best way possible for beings who, by our nature, are essentially partial, as discussed above. Through them, at each and every moment, our life can become a blót.

(As a methodological note, we have an interesting hint of the way that what appears merely as a common, shared attribute or background practice, belonging indifferently to many Gods in one theology, may come into focused centrality, in the person of a particular Goddess or God, in another theology. This suggests a fruitful ground for reflection and meditation on the relationships between metaphysical principles on one hand, and divine persons on the other — where we would do well to keep in mind Proclus’ axiom that the Gods are “first according to nature,” and thus their fields of commonality and interrelation are always downstream from Who they are in themselves.11)

IV. “All Things Pray, Except the First”

Let’s return to Neil Price’s perplexity, with which I opened this essay. The key assumption behind his remark seems to be a presumed upward trajectory of prayer. It’s quite reasonable to expect prayer to be directed to a superior of some sort. We can think here of (now mostly archaic) uses of ‘pray’ in English, as when we ask “What, pray tell…?”, or in the nearly obsolete word “prithee” (which is a contraction of “I pray thee”). Prayer is first of all just such an address, especially in a formal or reverential mode, acknowledging the other’s dignity in whatever sense. And something like this deference is certainly present in the divine symposia, assemblies, and other such gatherings of the Goddesses and Gods, that we find in so many theological traditions.

Yet this upward trajectory need not, as centuries of monotheism have conditioned us to expect, lead only to a single point that always and in every way dominates all the others. The relevant superiority might instead be contextual or perspectival, such that in this particular interaction, one person appropriately honors or defers to another, without eliding whatever complexities there may be between those two parties in other encounters, or in their status “taken overall.” By way of an all-too-human analogy, consider how a mechanic defers to a medical doctor in matters of healthcare, while the doctor defers to the mechanic in matters of car repair. Though if we’re to extend this to the Gods, we’ll need to be careful that (contra the human case) neither party is being diminished through the comparison.

In his Commentary on the Timaeus, Proclus cites with approval a maxim attributed to Theodore of Asine, that “All things pray, except the first.” We should not, I think, see this as the kind of “crypto-monotheism” that lurks behind Neil Price’s search for something “above the Gods,” nor even as a “tendency” in that direction, as scholars of the Platonic tradition sometimes suggest.

Let’s bring together the account of the various divine chains or series that we’ve explored in section II above, with the impossibility of a “one itself” that I have explored in a previous essay in this space. Considered in him- or herself, every God is first, standing as the source or fountain from which a certain stream flows forth through every level of being. By offering some of the water from that stream to another God, we see the God who makes the offering recognizing, even hymning, the primacy of the recipient as the leader of her own series — that is, recognizing the other God as a God. Thus, every God is first, and every God makes offerings to, and prays to, every other God (at least within the community of any “pantheon” or theological tradition).

In making such a claim, we are not reducing or limiting the Gods, but rather, exalting them. Every God is first, in his or her own uniquely incomparable way. For as Plato told us in the passage from the Phaedrus, “there is no envy among the Gods,” which Dronke echoes in her remark (p. 38) that the Gods have “no rivalry.” This helps us in making sense of the Met curators’ account of the Attic paintings, when they emphasize the ambiguity of agents and recipients for these divine libations.

Returning then to Theodore’s remark, we can understand that every God is the recipient of prayers and offerings, insofar as (s)he is first, and also the giver of offerings, as she recognizes her fellow Gods as also being first, each in their own way. When the Gods make offerings, we can see them presenting something of their own, something worthy and valuable, to another God, honoring and exalting that God, and in a mysterious way, being hallowed thereby. And in the blood-sacrifices poured out through Freyja’s agency, it becomes all the more clear that they are recognizing one another, not merely in a general way, but specifically as Gods, since it is only when given to a God that such a sacrifice could be appropriate.

We have, then, the three key moments in the Platonic understanding of what it is to be a God, and of what it is for the Gods to constitute being, at every level. First, we find each God in him- or herself, considered as supreme, total, and self-complete; next, the mutual recognition by the Gods of one another on Idavoll Plain or in the divine banquet of the Phaedrus, and their giving of offerings to one another there; and finally, the paradigm, through the contemplation of which the Gods create or constitute the cosmos. The first of these is the Intelligible order, and in particular, the first of the three triads that comprise this order. The second is the Intelligible-and-Intellectual order, which is anticipated in, and made possible by, the second intelligible triad. The contemplative activity of the third characterizes the Intellectual order, made possible by a paradigm in the third intelligible triad. This three-fold structure will echo through all levels of reality, in a manner appropriate to each.

The spaces of reciprocal divine encounter, then, are known to the Platonist as the intelligible-intellective order, and insofar as Freyja’s activity in some way12 makes possible such an intelligible-intellective space of mutual encounter between the Gods as Gods, the Platonist will see her as operating according to the second intelligible triad, which anticipates that order. Edward Butler describes that triad as follows: “The class of Gods who operate according to the second intelligible triad perform a mediating and relating function for the other Gods who proceed with them and after them, and for the cosmos they constitute together.”13

Both aspects of this are relevant to the Goddess who is the divine blótgyðja: mediation between the Gods themselves, and the constituting of the cosmos by the Gods. For even the sacrificial rites performed down here by us mortals, in emulation of those done by the Gods, are traditionally understood to play a critical part in creating and sustaining the worlds. So too, when we ourselves become the offerings made by the Gods, we come to participate in — even partially to constitute — their mutual recognition of one another, in some even more mysterious way.

V. Some Conclusions

What a beautiful thing, to be the gift, the prayer, the offering given by a God. Right there, we have a mystery which, like every truly sacred mystery, is wonderful and awful (awe-full) and holy.

And yet, there’s more, when we recognize the prospect of doing this mindfully, as fully and consciously as we can. What does it mean when we’re able to perfect such an offering from a God to a God, by partaking willingly and knowingly of Freyja’s mysteries, by deliberately allowing ourselves to be offered in this mysterious and wonderful way? What does it mean that we can do this again and again, throughout a lifetime and across many lives? Can we become both the sacrifice and the altar, such that our own hearts are transformed from stone to brilliant, translucent glass, as the humble stone altar of Óttar, Freyja’s simple but pious devotee, was, through the intensity of his offerings?14

I invite you, dear reader, to take these things — these images, these mythic episodes, these philosophic and interpretive possibilities — to heart. Meditate upon them, contemplate them, ponder and consider them, and see what emerges. For I’m quite confident that these are rich, bounteous, overflowing springs, from which this essay has channeled only a small portion of the waters. And I’m sure that there are adjacent mysteries, as it were, in other theophanic traditions, each of which will have something singular, unique, and wonderful to offer to the initiates and devotees who approach them.

This is why I study and teach the Platonic tradition. Because for myself and for some others, it can be the springboard for this sort of deep and extended theological reflection, that helps me draw closer in devotion to my Gods. Coming to them by this means is a source of joy, and wonder, and delight. I hope some of those qualities have managed to shine through, in whatever degree, in the reading of it. It’s certainly not the only way that we can approach the Gods, nor is it the only way that I myself approach them. And while it’s certainly not a requirement for everyone, I do believe that such philosophic exploration of our theology has something unique to offer to our traditions at large, which is in some way unique, never quite reduceable to other ways by which we approach them.

Neil Price, The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings (Basic Books, 2022), page 50.

We should note that 12 is a symbolic number, conveying a sense of totality or all-inclusiveness, rather than giving a definitive census of exactly how many Gods there are.

The Poetic Edda, Volume II; Mythological Poems, edited with translation, introduction, and commentary by Ursula Dronke (Oxford, 1997), page 37.

Here, the Platonist will call to mind the opening paragraph of Sallustius’ 4th-century treatise, On the Gods and the World:

It is requisite that those who are willing to hear concerning the Gods should have been well informed from their childhood, and not nourished with foolish opinions. It is likewise necessary that they should be prudent and good, that they may receive, and properly understand, the discourses which they hear. The knowledge likewise of common conceptions is necessary; but common conceptions are such things as all men, when interrogated, acknowledge to be indubitably certain; such as, that every God is good, without passivity, and free from all mutation; for every thing which is changed, is either changed into something better or into something worse: and if into something wose, it will become depraved, but if into something better, it must have been evil in the beginning.

His argument for the very claim we’re interested in — Gods’ immutability; that is, their impassive or unchanging nature — is well worth meditating upon.

In Greek, symbola (singular symbolon).

Here and throughout this essay, I use the term ‘proper’ in its oldest, very traditional sense, to mean “that which is one’s own.” It’s from this original sense of ‘proper’ that we get the term ‘property.’

Republic X, 617e.

Republic X, 618a.

I’ve discussed this axiom in section 2 of this previous essay.

I make frequent use of hesitating phrases like “in some way,” from a desire to preserve the proper place of theophany — and the irreducible uniqueness of each theophany — prior to (or upstream from) the categorization and classification that is the work of philosophy. We should always keep in mind that any commonalities we observe between Gods, whether across pantheons or within a single theological tradition, are always downstream from each individual God or Goddess in him- or herself. The Gods are not manifestations or instantiations of the categories; rather, the categories flow from the many individual Gods. In terms of the three orders mentioned above, we find the individual Gods at the Intelligible order, while the philosophical categories only become apparent at the Intellectual order.

“The Second Intelligible Triad and the Intelligible-Intellectual Gods,” in Essays on the Metaphysics of Polytheism in Proclus, pp. 128–129.

Cf. Hyndluljóð, v. 10.

Beautiful !