Honoring our Platonic Ancestors: The Life of Proclus

“The primary good is not contemplation...”

A very warm welcome to all my new readers and subscribers! Thank you for your interest and support of this work. I’ll be back later this month, to continue the exploration of self-knowledge begun in the last essay, and to extend this into an exploration of the stages of prayer. In the meantime, tomorrow is a meaningful anniversary for those of us who carry on the Platonic tradition, so I’d like to take a few moments to reflect on that, and to honor an exemplary ancestor.

Tomorrow, February 8th, is the traditional date of the birth of Proclus, one of our most illustrious predecessors in the Platonic tradition. Born in 412 CE, he was educated in rhetoric and law before dedicating himself to the study of philosophy, amidst social and political circumstances that, in many respects, sound all too familiar to the world we live in today.

Proclus completed his Commentary on the Timaeus at the the age of 28. The work runs to around 1,000 pages in English translation, and includes the sort of detailed summaries of his own predecessors’ views that, in many ways, make it the equivalent of a modern doctoral dissertation.1 And indeed, it was shortly after completing this work that Proclus became the head of the Athenian Academy, upon the death of his preceptor Syrianus.

His other works include two sweeping and magisterial theological works: the Platonic Theology, and his Commentary on the Parmenides, as well as various other commentaries, short essays, and hymns. Of the latter, his biographer Marinus indicates that Proclus composed a huge number of hymns, to Gods and Goddesses both popular and obscure, of which only seven survive today.2

He completed these written works while also teaching and lecturing extensively, sometimes (Marinus suggests) giving as many as five lectures in a day, all without neglecting his devotions and ritual purifications, which he maintained with zeal and diligence throughout his life, until his death on April 17th, 485.

All of this was carried out under, shall we say, far less than auspicious circumstances. In the 5th century CE, Proclus and his contemporaries were living in a crumbling empire, which had long-since overshot its resource base, with the constant threat of external military conflict, civil war, and mob violence. All the while, a fanatical religious minority was trying its utmost to co-opt the machinery of the state to enforce its genocidal agenda on their fellow citizens and their holy places.

Proclus himself, Marinus tells us, had to make a hasty, year-long departure from Athens when the prevailing circumstances got a bit too hot. Yet he was able to turn even this into an extended pilgrimage, deepening his initiatory connections with the Gods of the nations to which he traveled — not merely a shallow “spiritual tourism,” as some modern (atheist) scholars would have it, but a pious seeking to use every opportunity to draw ever closer to the Holy Ones who are the fountains of all good.

As heirs of his impressive legacy, we should certainly celebrate Proclus’ achievements as a philosopher, a theologian, and a theurgist. And in doing so, we would do well to remember that these achievements were not in any way the marks of withdrawal from caring for his community and the mundane world around him. Rather, his philosophic and theological work connected him with the fountains from which such care can flow most fully and effectively. As Proclus himself writes in his treatise On the Subsistence of Evils:

The primary good is not contemplation, intellective life, and knowledge, as someone [i.e., Aristotle] has said somewhere. No, it is life in accordance with the divine intellect which consists, on the one hand, in comprehending the intelligibles through its own intellect, and, on the other, in encompassing the sensibles with the powers of the circle of difference and in giving even to these sensibles a portion of the goods from above. For that which is perfectly good possesses plenitude, not by the mere preservation of itself, but because it also desires, by its gift to others and through the ungrudging abundance of its activity, to benefit all things and make them similar to itself [in goodness].3

To judge by Marinus’ biography, Proclus lived by this principle. He was constantly turning to the Gods in prayer, in sacrifice, in purifications and offerings, and by doing so, he was filled to overflowing with their gifts. These gifts flowed forth through him at every level, from his pious hymns and inspired theological writings; to the political advice he offered to the statesmen of Athens, both directly and through his dear friend Archiadas; to the very physical miracles he effected, both for the healing of individuals, and for averting drought and other disasters from the community. Proclus was active in all these ways, not from any calculating or mercenary motive, but just because that’s what the Gods do, and so this holy teacher quite naturally did likewise, as he strove, in the words of Plato’s Theaetetus, to become God-like insofar as possible for a human being,

We can and should marvel at everything this great and inspired predecessor was able to accomplish, under such trying circumstances. Yet we might also ask whether these circumstances, in some way, actually provided the very impetus to his excellence. Near the start of his 1788 essay “On the History of the Restoration of the Platonic Theology,” Thomas Taylor (another of our illustrious predecessors in the tradition) suggests as much:

It appears at first view strange that this sublime theology should rise to its pristine perfection during the decline of the Roman empire; and at a period when a new religion (I mean the Christian) was continually increasing in reputation, and advancing with rapid steps to a despotic establishment. But if we attentively consider, we shall find that the very causes which apparently threatened its destruction were the natural and proper sources of its renovation. As every part of the universe subsists by perpetual change, it is necessary that philosophy and the sciences, with respect to their appearance or the contrary, should share in the general mutability of things: but at the same time, it is necessary to their preservation to after-ages, that the order of their revolution should be retrograde to that of sensible particulars. Hence we shall often find, that while kingdoms descend in the circle of vicissitude, philosophy ascends, and perhaps attains to her ultimate perfection, at the very period when the most powerful nations become extinct.

Thus the falling empire of the Romans was naturally connected with the rising greatness of philosophy; and the foreign ceremonies of a new religion, were the proper means of bringing to light the secret mysteries of the old. We may add too, that the same circumstances produced the great difference between the first and last appearance of this sublime theology. While Greece maintained her independence unconscious of the Roman yoke, and undisturbed by religious invasions, she disdained to expose her genuine wisdom to vulgar inspection, but involved it in the intricate folds of allegory; and concealed it from the profane under the dark veil of impenetrable mystery. But when she lost her liberty and submitted to foreign domination, when her most ancient rites were threatened with invasion, and her sacred mysteries were treated with contempt, she found it necessary to change the dress of theology and to substitute a simple and elegant garb, instead of one highly marvellous and mystic.

At the very least, we might ask ourselves: How can the times in which we live be the impetus for us to emulate the life of Proclus? First and foremost, in turning ever more fully and deeply to the Holy Ones, and secondly, in allowing their gifts to flow through us, in our devotions, in our theological and philosophical studies, and in our providential care for those around us?

This nativity, I might add, is but one occasion among many for honoring our Platonic ancestors. In my own practice, there are a number of other festive and memorial occasions which are tied closely to the received tradition, both from antiquity and from more recent centuries. I list them here, as invitation and inspiration to others.

The Nativity of Proclus (February 8).

The Death of Proclus (April 17).

The Thargelia (based on the Athenian lunar calendar; in 2025, May 4 & 5, beginning at sundown the evening before). The traditional dates of the births of Artemis and Apollon, respectively, are also the dates of the birth of Socrates, and of both the birth and death of Plato. Though concerned especially with the Goddess and God, and with various rites of purification, they are also important days to honor these founding human figures of the Platonic tradition. The Anonymous Prolegomena to Platonic Philosophy informs us that on this occasion, the people of Athens were accustomed to sing a hymn which began “On this day, the Gods gave Plato to mankind.”

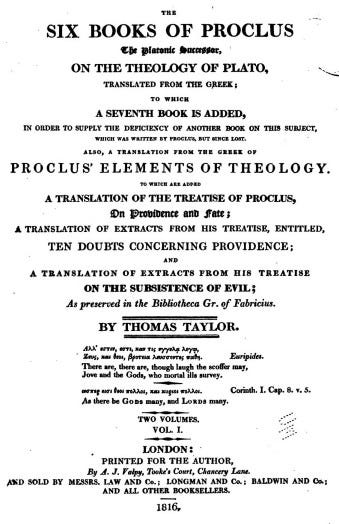

The Nativity of Thomas Taylor (May 15). Very much like Proclus, Taylor (1758–1835) displayed incredible dedication to the Platonic tradition under extremely adverse personal circumstances. Despite poverty and the challenges of health and material constraints, he managed to produce the first complete English translations of all the works of Plato, all the works of Aristotle, and many of the great Platonic commentaries, including Proclus’ Platonic Theology and Timaeus Commentary in their entirety, along with substantial extracts from many others. He not only translated these works, but displayed a deep, even preternatural understanding of the subtleties of the philosophy contained therein.

The Wounding & Death of the Emperor Julian (June 26 & 28). As well as being a pious and faithful emperor, who strove mightily to maintain and restore the worship of the Gods, Julian was also well-trained as a Platonic philosopher. His philosophically-informed piety is especially evident (among his surviving works) in two quite lengthy prose “hymns”: to the Sovereign Sun, and to the Mother of the Gods.

The Death of Thomas Taylor (November 1). I honestly don’t do much explicitly for this one, since other observances for the dead in general and the turning of the season generally take precedence on this date, and given that the biggest feast of all for my Platonic ancestors is coming in less than a week. But I note the date here for others.

The Platoneia (November 7). This is the big one. As noted above, Plato’s birthday is traditionally reckoned according to the Athenian lunar calendar. That calendar begins with the new moon following the summer solstice, and Plato’s birthday is the 7th day of the 11th month of that calendar, which usually falls sometime in our month of May. During the Italian Renaissance, however, the Florentine Academy that gathered around Marsilio Ficino and his circle celebrated Plato’s birthday not according to the Athenian calendar, but on the 7th day of the 11th month of our own modern calendar, that is, November 7. Especially given the way that the whole month of November, in so many Northern-hemisphere traditions, is a time for honoring the dead, I and others have found this to be an excellent day to celebrate all of our ancestors in the Platonic tradition, both known and unknown.

I hope to write more about at least some of these observances as we draw near to them in the course of the year. For now, I offer at least this minimal listing, for those who may wish to plan ahead.

We owe so much to all of our ancestors, both the biological and adoptive families who have given us our natural endowments, and our ancestors of intellectual, philosophic, and spiritual lineages, who have gifted us with their wisdom, with their examples of pious study and devotion, and with the means by which to draw nearer to the Gods, who are the source of all good.

Proclus himself offers one of the greatest testimonies to the importance of venerating such ancestors and teachers. His own teacher Syrianus, who adopted him into his household, died when Proclus was still quite young, likely in the early 440s. Proclus praises his teacher verbally in many places throughout his works, including in the prayer which begins the Parmenides Commentary, where he addresses Syrianus as “thou, who art truly agitated with divine fury, in conjunction with Plato, who wert my associate in the restoration of divine truth, my leader in this theory, and the true hierophant of these divine doctrines.” But all the more movingly, in acknowledgment of the deep and abiding debt he owed to Syrianus as his teacher and initiator in the mysteries, Proclus arranged that upon his own death, nearly a half-century later, his mortal remains would be laid alongside those of his teacher in a single tomb.

Somewhat off the topic of this essay — though relevant to the divine fury with which Syrianus, Proclus, and all of the greatest teachers in the Platonic tradition have been filled — I’m happy to announce a new publication which may be of interest to readers of these essays.

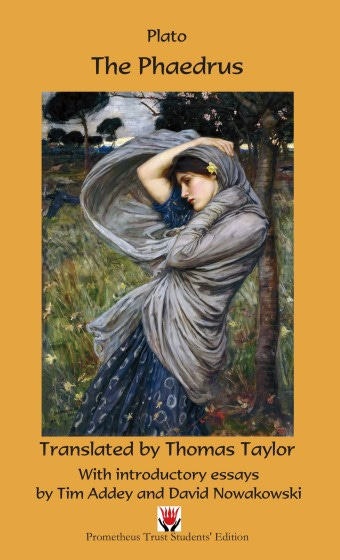

Plato’s Phaedrus is arguably the most beautiful of all his dialogues. This comes as no surprise, since the subject of the dialogue is Beauty in all its varieties, at every level of the cosmos: from the nymph-haunted grove in which Socrates and Phaedrus have their conversation, to the beauty of human bodies (young Phaedrus was exceptionally handsome!), to the beauty of speech and discourse (both mythic and scientific), to the beauty proper to human souls (their knowledge and virtues), to the intelligible and divine beauty at the summit of all these. In the course of this wide-ranging inquiry into beauty, Plato addresses a variety of related themes, including the activity of love, and the divine madness (or mania, fury, etc.) that can elevate us above a merely rational nature to share in a divine life.

As part of their Students Editions series of paperbacks, the Prometheus Trust has just released a new edition of the Phaedrus, which includes a lightly-revised version of Thomas Taylor’s translation of the dialogue, along with a half-dozen interpretive essays, written by Tim Addey and myself, which are intended to help beginning and intermediate students approach some of the intricacies of the work. The six essays include:

The Scope and Structure of the Phaedrus

Hermias on Inspiration

A Platonic Demonstration of the Immortality of the Soul

Self-motion in Metaphysics: Descent and Ascent

The Journey of the Soul

The Oral Tradition in Platonism

It’s available now, in the USA from me at Kindred Star Books, and in the rest of the world directly from the publisher.

It also breaks off somewhat abruptly, well before getting to the end of the Platonic dialogue. This too is like many Ph.D. dissertations. As my own advisors told me at around the same age: “The best dissertation is a done dissertation.”

Marinus’ biography of Proclus is extant, and available in at least three different English translations. Thomas Taylor’s translation is included in Essays and Fragments of Proclus (volume 18 of the Thomas Taylor Series from the Prometheus Trust, available in the USA from me here; in the rest of the world, direct from the publisher here). Other more recent translations are also available online and in print. An early-20th-century version by K.S. Guthrie (likely based on that of Taylor) is available here — this site overall is an admittedly awkward resource, but this public domain text seems to be fine. A still more recent translation (which I have not consulted) is in Mark Edwards, Neoplatonic Saints: The Lives of Plotinus and Proclus by their Students (Liverpool University Press, 2000).

The seven hymns have been translated with extensive and astute commentary by R.M. van den Berg, in a very expensive volume simply entitled Proclus’ Hymns: Essays, Translations, Commentary (Brill, 2001). I recommend turning to a nearby university library, or to interlibrary loan, for this one.

Proclus, On the Existence of Evils, section 23. Translated by Jan Opsomer & Carlos Steel (2003). I’ve incorporated the translators’ bracketed additions into the main text (without brackets); the glosses in square brackets given here are my own.

This is really beautiful David. Thanks for sharing, and thank you for making it that much easier to honor our polytheist ancestors!

Thank you for this timely and inspiring reminder of Proclus, his brilliance and unstinting generosity.